Resistance

There is always resistance to violence. South Texas experienced deep violence as an area open for dispute by colonial imperial powers, as an area salivated by the U.S empire and the doctrine of Manifest Destiny, the brief independence of Texas who wanted to uphold the institution of slavery, and the institutions of the Texas Rangers and the Border Patrol who were formed to “pacify” Mexicano rebels and “bandits”. The following sections are not the only historical accounts of resistance, but each will give you an introduction into important events of resistance in South Texas.

The Underground Railroad

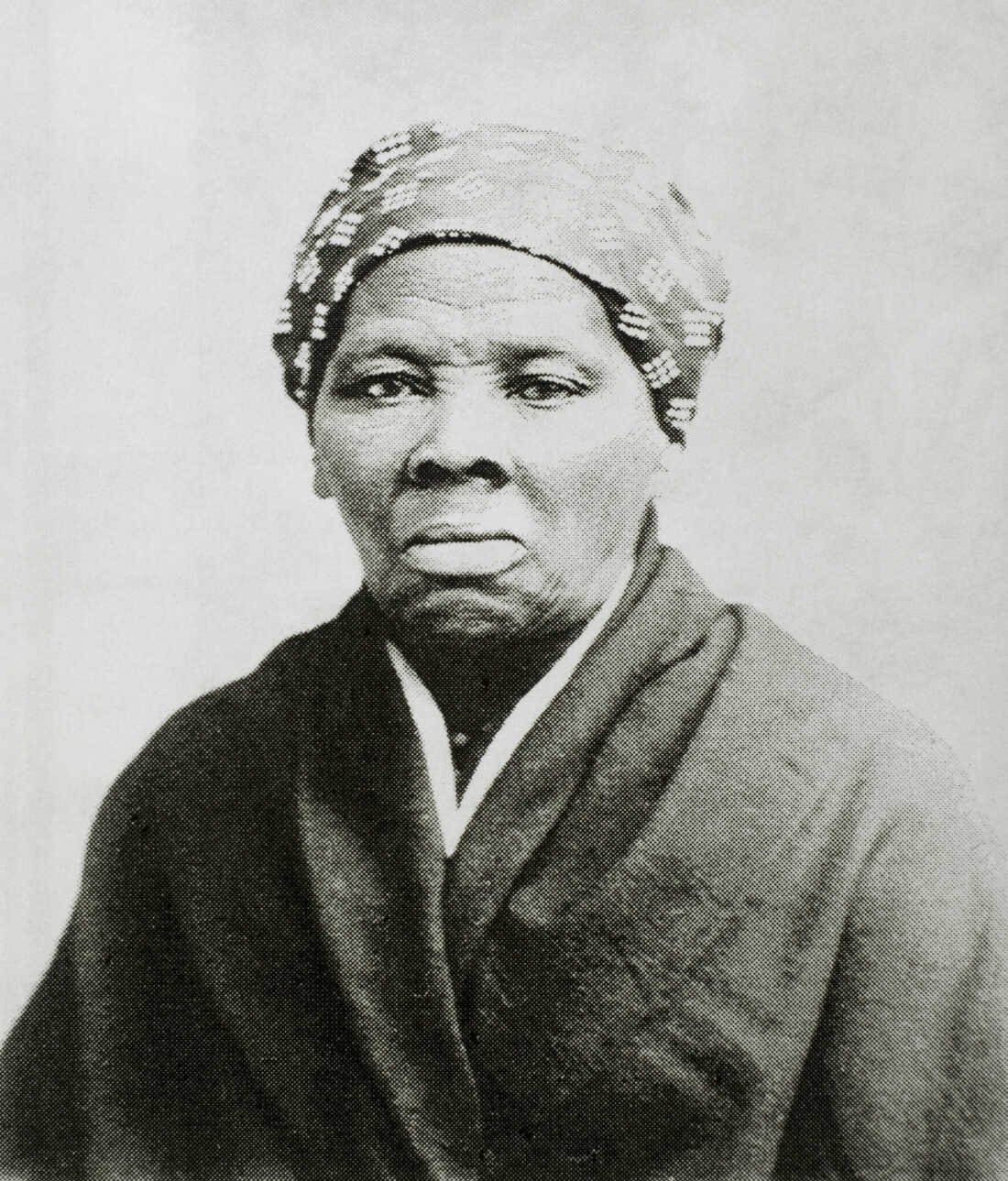

Harriet Tubman, Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images

Mexico outlawed the institution of slavery decades before it was abolished in the United States. Abolitionist and activist, Harriet Tubman, escaped slavery by using networks of abolition activists and safe houses known as the Underground Railroad. Harriet Tubman made many trips to the south to help other enslaved black people escape including her own family and friends. Tensions grew between the northern and southern states before the civil war, which led to a passing of a group of laws known as the “Fugitive Slave Acts”. This gave so-called “slave catchers” the legislative right to enter the north and retrieve “alleged” runaway slaves. (Juan Carmona, interview, September 15, 2023) Fearful of capture, formerly enslaved people looked to Mexico as refuge. Afro-Mexican second president of Mexico, Vicente Guerrero abolished the institution of slavery in 1829, and it became a law in 1837. At this time, in what is now Texas, anglo settlers claimed to be oppressed by Mexico, who did not align with their own “democratic” ideals. These “democratic ideals” for Anglo Texans meant the “right to protect” the institution of slavery.

Vicente Guerrero, A half-length, posthumous portrait by Anacleto Escutia (1850), Museo Nacional de Historia.

Enslaved people in Texas had a possibility of escaping through the south, through the Rio Grande Valley to Mexico. The terrain was tough and dangerous to navigate, the South Texas brush that today still threatens the lives of migrants today. According to Nosotrxs Por el Valle, a group of RGV historians, The Webbers and the Jacksons were two mixed race families who both owned ranchers along the Rio Grande River and operated ferries, which they would use to safely cross escaped enslaved peoples into safety in Mexico. (Juan Carmona, interview, September 15, 2023)

The Cortina Wars

William H. Emory, (Archival Photograph by Mr. Sean Linehan, NOS, NGS) - "United States and Mexican Boundary Survey. Report of William H. Emory ...." Washington. 1857.

After 1848, the area known as the Rio Grande Valley Delta became part of the United States. The new anglo investors allied with local authorities and manipulated the political system to lay the grounds for anglo stripping of lands and accumulation of wealth. The Texas Rangers intimidated Mexican landowners to sell, often killing men, and making their widows surrender their lands. Juan Cortina’s family at the time owned much of the land in what is now Brownsville, Texas. Juan Cortina shot the city Marshall for violently mistreating a servant of his mothers. In 1859, Cortina along with 70 men occupied the town of Brownsville, resisting Anglo dominance and Texas Ranger violence. This is now known as the first Cortina war with the second following in 1861. Cortina escaped to the Mexican side of the border, and the Civil War began, which made it easier for him to evade capture. Cortinas would begin to operate from the Mexican side, fighting with the Union against Confederate soldiers. Porfirio Diaz imprisoned Cortinas and he died in prison in Mexico in 1894. Dictator Diaz also wanted to pacify the border, cooperating with the U.S, any men that would flee to Mexico would be returned to U.S soil through the Porfiriato dictatorship. (see Wikipedia, Cortina Wars)

El Plan de San Diego

In 1915, Bacilio Ramos traveled from San Diego to South Texas, where he was captured and arrested by the Texas Rangers for a document he would be holding close to his guard. The document was a manifesto, el Plan de San Diego. (Juan Carmona, interview, September 15, 2023)

El Plan de San Diego called for a “Liberating Army for Races & Peoples” to kill every white male over sixteen years old and to seize Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and California. The first lands to be seized were to be given to African Americans and Indigenous communities to build for themselves independent nations– sanctuaries–free of Anglo-American domination.

-Kelly Lytle Hernández, (3, Bad Mexicans, P. 298)

That same year, groups of Mexicans and Mexican Americans started killing white men under the name of El Plan de San Diego. According to Kelly Lytle Herández, author of Bad Mexicans, El Plan de San Diego was one of the largest and deadliest uprising against white settler supremacy in US History. And it is not very well known and of course never part of our history classes in South Texas. (3, Bad Mexicans)

In retaliation the U.S army sent 4,000 troops into South Texas, and together with the Texas Rangers committed mass murder of Mexicans and Mexican Americans, this would be known by scholars as La Matanza. These mass killings and lynchings would send ripples of terror into Mexican and Mexican American families in South Texas. (See Violence on the South Texas Border)

The Magonistas y el Partido Liberado de México

1916, Ricardo and Enrique Flores Magón at the Los Angeles County Jail.

En la fotografía aparecen: Federico Pérez Fernández, Santiago de la Hoz, Manuel Sarabia, Benjamín Millán, Evaristo Guillén, Gabriel Pérez Fernández, Juan Sarabia, Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama, Rosalío Bustamante, Tomás Sarabia y Ricardo y Enrique Flores Magón. Mexico City, 1903.

In her book, Bad Mexicans (3), Kelly Lytle Hernandez states the important role south Texas had in the shaping of the United States. She writes that the violence on the south Texas border, the rise of imperialism, and white supremacy at the turn of the 20th century led to an uprising that sparked the Mexican Revolution.

In Mexico, Porfirio Diaz, the once hero of the Battle of Puebla (1862), rose to power as a dictator. Bypassing the Mexican Constitution law of limiting presidential terms in power, Porfirio Diaz stayed as president for 30 years. This period is known in history as the Porfiriato. (3, Bad Mexicans)

During the Porfiriato, Diaz used “rurales”, a rural police force, to violently appease and control the Mexican resistance. The “rurales” were responsible for committing mass violence in small rural areas and violently killed and displaced Yaqui people in Mexico.

Porfirio Diaz opened the doors for the US. Investors in Mexico that together with the railroad connection to the United States from central Mexico flooded Mexico with US dollars. (3, Bad Mexicans) U.S. investors purchased about 130 million acres, nearly a quarter of the Mexican landbase, said Kelly Lytle Hernandez in a Democracy Now interview.

“US investors come to dominate key Mexican industries, like railroad, oil, mining, and more. And it is that invasion of US dollars and also European dollars that displaces millions of mexican peasants, community folks, rural folks, indigenous populations. They become displaced, become wage workers and then they begin to migrate into the United States in search of work. This is the beginning of mass labor migration between the US and Mexico.” - Kelly Lytle Hernanez, Democracy Now Interview

Ricardo Flores Magon and his brothers were journalists in Mexico, and published a newspaper called Regeneración, in which they called Porfirio Diaz a dictator and said that Mexicans became the servants of foreigners. At the time, there was no public denunciation of the Diaz regime. Diaz had Flores Magon arrested multiple times and imprisoned him in one of the harshest prisons in Mexico. A gag, prejudiced rule was issued, which restricted any free speech against the Diaz regime, so Flores Magon and his group were obligated to look for a safer location and crossed the US Mexico border through Laredo, Texas.

In the United States, Flores Magon and his group of socialists/anarchists established el Partido Liberado de México and built a small army. They raided Mexico four times and were able to destabilize the Diaz regime. The US reacted as it wanted to protect their economic investments. The Magonistas and PLM army incited the outbreak of the 1910 Mexican Revolution. (3, Bad Mexicans)

One of the insurgency leaders of El Plan de San Diego was Ancieto Pizaña, who was also a part of the Partido de Liberado de México. Pizaña met Ricardo Flores Magon in Laredo, Texas in 1904. The parallels seen between the Diaz regime rurales and the Texas Ranger and anglo violence created more collective resistance. (3, Bad Mexicans)

In 1916, both Flores Magon brothers were convicted and imprisoned for publishing their support of the Plan de San Diego and violating the Espionage Act. U.S Authorities viewed Ricardo Flores Magon and his anarchist and revolutionary ideas as a threat. Ricardo Flores Magon died in prison and his brother, Enrique Flores Magon went on to document and archive his story, as one of the key people that incited the Mexican Revolution. (3, Bad Mexicans)

JT Canales

In 1919, José Tomás Canales, the only Mexican-American legislator in Texas, and State Representative for Brownsville, was dismayed by the violence happening in his district. He suspected there was an abuse of state power and that the Texas Rangers were acting with impunity. (White Hats Podcast) Canales filed a request for witness testimonies and hearings. His intention was to restructure the force and prevent any more unlawful violence. This was the first time these mass murders were discussed publicly. Canales used his state position to bring accountability to the force in order to reform it. The Texas Legislature hearings heard the testimonies of more than 90 people, that detailed evidence of killings, torture, and harassment at the hands of Texas Rangers. (White Hats Podcast)

The Texas Ranger fired a counterattack and claimed that its force was necessary within an unstable and violent South Texas. The lawyers who represented the Texas Rangers claimed that Mexicanos were inherently violent and in order to control these populations, the Texas Rangers were obligated to use force. (White Hats Podcast)

The transcripts of the Canales hearings were sealed for 50 years, since the Canales investigation had been closed. In 1975, James Sandos, uncovered the transcripts and the archivist told him that the last person that had seen the transcripts was Walter Prescott Webb in 1919. Walter Prescott Webb shortly after went on to write a history of the Texas Rangers, called The Texas Rangers: A Century of Frontier Defense, one where he made the Texas Rangers, and his friend Hammer into heroes and legends. Hollywood then made a movie based on his book called The Texas Rangers. Monica Muñoz Martinez, Mexican American History scholar and founding member of Refusing to Forget, says that Webb knew about the violence. She adds, he is not telling the story from the point of view of people who were massacred. He’s telling it from the point of view of the Texas Rangers. And so he’s justifying their actions. (White Hats Podcast)

Jovita Idar

Helaine Victoria Press, Jovita Idar (1885-1946) [postcard], 1986. W075_029, Feminist Postcard Collection, Archives for Research on Women and Gender. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University.

Jovita Idar was a feminist journalist based in Laredo, Texas. Her family’s weekly newspaper, La Cronica, was the only publication documenting the lynchings and violence in the region. (3, Bad Mexicans) Jovita’s father had taught her that as a family they had an obligation to “fight for the Mexican people.” (3, Bad Mexicans)

Jovita and her family wrote extensively about Texas Ranger violence and the Canales hearings. Their newspaper also covered the threats and discrimination that JT. Canales faced during and after the hearings at the Texas capital.

In 1914 in Laredo, Jovita Idar bravely stood in front of the entrance of El Progreso press when a group of Texas Rangers tried to enter with the intention of destroying the printing press. This happened after the newspaper wrote a criticism of President Woodrow Wilson's order to send U.S military troops to the U.S Mexico border in order to pacify the “bandit violence” . The Texas Rangers came back the next day and before she arrived, they destroyed the press and arrested a few of the workers. The Progreso Press did not stop. They continued publishing many front page news articles, including following the case on Gregorio Cortez.

The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez: Corridos as a form of resistance

Image courtesy of the Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

In 1901, on a ranch west of San Antonio, County Sheriff William “Brack” Morris wrongfully accused Gregorio Cortez of horse theft. Morris led the Rinches on a humiliating manhunt across the borderlands. (3, Bad Mexicans) In the attempt to arrest Cortez, Sheriff Morris killed his brother and Gregorio shot the Sheriff. After that, Gregorio had to flee to save his own life.

For many Mexican Americans across Texas, who knew of the histories of oppression and violence and racism, Gregorio Cortez became a folk hero. Mexican Migrant workers followed the case of Gregorio Cortez through hearing the corrido, imagining this folk hero as someone who fought off a more powerful enemy. (3, Bad Mexicans) Monica Muñoz Martinez of Refusing to Forget and author of The Injustice Never Leaves You (7, The Injustice Never Leaves You), says, corridos were the Mexicanos version of history, a story of survival. (White Hats Podcast)

Americo Paredes’s book, With a Pistol in his hand chronicles the life of Gregorio Cortez, was a direct challenge to Ranger mythology. (12, With a Pistol in His Hand) It presents the significance of the corrido as a form of resistance. Americo Paredes was born and raised in Brownsville, Texas. His writings helped inspire the Chicano movement. (White Hats Podcast)

References:

White Hats Podcast Texas Monthly podcast

3, Bad Mexicans

7, The Injustice Never Leaves You

12, With a Pistol in His Hand

Links:

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p1535.html