Index

© This research has been compiled by Nansi Guevara with the purpose of dismantling the narrative of there is nothing here, present and persistent on the South Texas border. This composition references her own expertise as a border artist and the work of borderland academics and experts who have dedicated their lives to understanding and dismantling white supremacist narratives on the South Texas border. We ask that you properly credit this work, and the work of these authors in your own research and writing, and maintain a collective mission to learn and unlearn, not extract.

Text written by Nansi Guevara, Ed.M and

edited by Miryam Espinosa-Dulanto, Ph.D.

Revised by Christopher Basaldú, Ph.D

Christopher Carmona, Ph.D.

and Juan P. Carmona

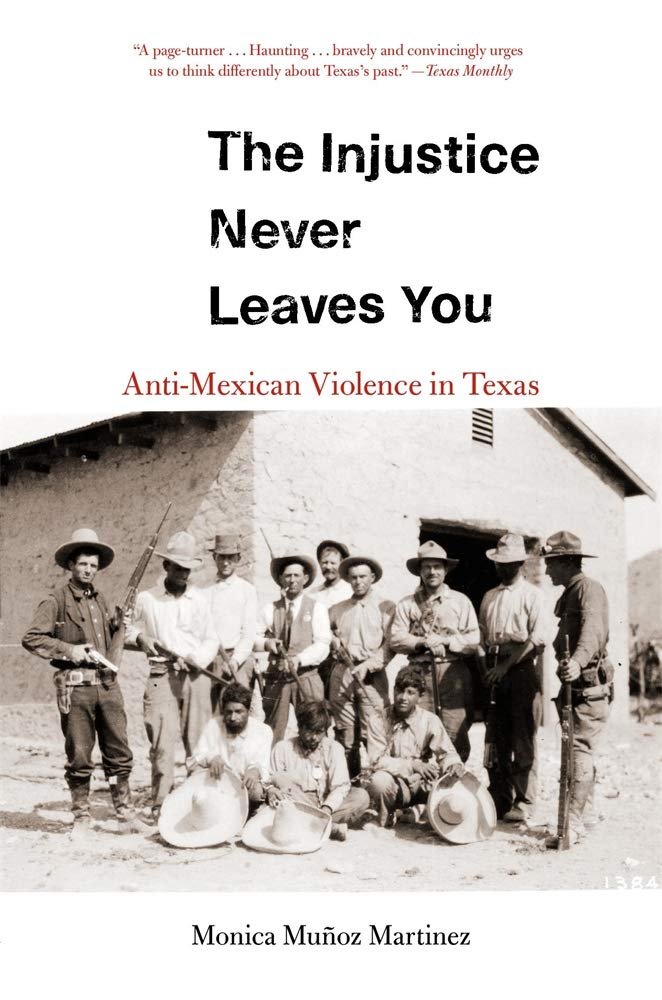

Dismantling Settler Imaginaries

Texas children were taught a white washed version of history, one that erased Mexicanos, Natives, and African American stories. The state of Texas has banned more books than any other state in the nation. The issue with erasing our history is that we, people of color, have internalized these narratives as true. Therefore, we have been robbed of our own personal and collective histories.

If you grew up on the South Texas border, the false narrative of there is nothing here permeated both in our self-identities and our understanding of the place we live. This is a common narrative that seeps into our daily lives and how we navigate our worlds. In addition, this false narrative invites us to leave. There is nothing here, so that means we are nothing, and we need to leave our community to become someone. Nuestra Delta Magica frames this false narrative as a direct result of the erasure of our history and the indoctrination of Anglo Texas history in Texas public education. “There is nothing here” stems from the systems of oppression of colonization.

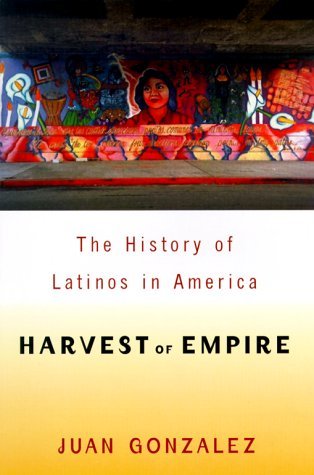

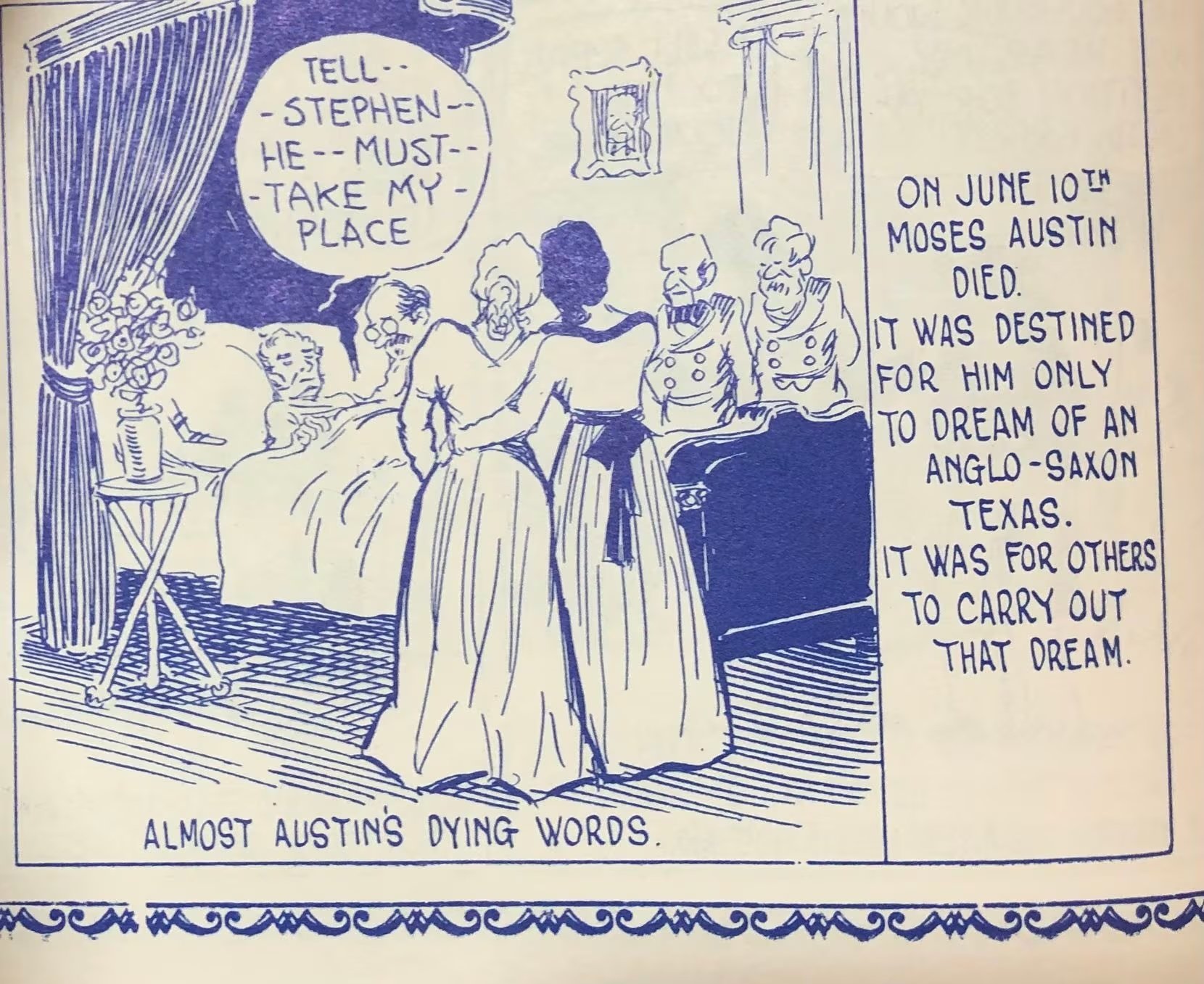

If you grew up in Texas, you might remember carrying a bible-size -Texas History textbook to your Texas history class and pledging to the Texas flag every morning. You might also remember having to memorize names of proclaimed heroes and fathers of Texas, like Stephen F. Austin and Davy Crockett. What we don’t remember is the erased history that would have told us that Stephen F. Austin was a founding member of the Texas Rangers, who committed state sanctioned violence against Mexicanos, and were known as “los Rinches”. (7. The Injustice Never Leaves You) Davy Crockett fought during Texas independence, at the battle of the Alamo, to keep the institution of slavery, which Mexico had already abolished. ( 10. Harvest of Empire )

Image from a racist comic strip that was run between 1926-1928 in the Dallas Morning News. It was published into a hardcover book and taught in Texas Public Schools for 30 years after that. (citation)

Comic strip written and illustrated by Nansi Guevara, titled, Nuestra Delta Mágica, addressing the false narrative of there is nothing here.

Most importantly, this exhibit will demonstrate how “There is nothing here” has been used throughout history to justify violence, extraction of land, and exploitation of brown, black, and indigenous labor in the Rio Grande Valley Delta.

This exhibit, at its core, is an invitation to learn about our own history in the Rio Grande Valley. We believe that if we learned our history, our violent and difficult history, as well as our history of resistance, we would understand ourselves better and would see our role in protecting the beautiful and abundant Rio Grande Valley Delta.

References:

7. The Injustice Never Leaves You, Monica Muñoz Martinez

10. Harvest of Empire, Juan Gonzalez

Links:

https://www.texastribune.org/2022/09/19/texas-book-bans/

https://www.dallasnews.com/news/watchdog/2021/12/17/for-decades-a-comic-book-showing-texas-history-in-the-most-racist-ways-was-given-to-texas-students/

This is Native Land

“Con conocer nuestra conexión a la tierra, podemos pelear por ella ”

-Juan Mancias, Tribal Chairman, Esto’k Gna Tribe of Texas

Climate in the lower Rio Grande Valley has been historically arid, with sporadic flooding periods. The Esto’k Gna and other indigenous groups of the Rio Grande delta have moved around and across the Rio Grande river freely for thousands of years. Juan Mancias, today’s tribal chairman of the Esto’k Gna tribe, (known as Carrizo Comecrudo), tells that originally the tribe came from the mouth of the river, la boca del rio. The water flows from Colorado, washing down with the beauty and abundance to create the first woman.

The Rio Grande delta at Boca Chica beach is an ancestral sacred land for the Esto’k Gna Tribe, who is fighting hard to protect sacred land from LNG or (Liquified Natural Gas pipelines) and SpaceX. “We have this ritual,” Juan says, “when a baby is born, we bury the umbilical cord. This is so that our descendants never forget where they came from, they came from the land, the earth. If we know where we came from, we can know how to protect the land and fight for it.”

This is a reminder that we come from the land, and we need to work to protect it. Juan Mancias, says the Esto’k Gna were the first people enslaved by the Spanish in these lands through their encomienda system. Missions and encomiendas set up a system to violently convert indigenous population into Catholicism to steal the resources of the land and the labor of the people. Furthermore, Juan shares a local Spanish saying, patas rajadas, that refers to the Spanish invaders practice of cutting off the feet of the Carrizos who refused to convert to Christianity.

Christopher Basaldú, PhD, Tribal member of Esto’k Gna, explains that the river is more like a road than a wall or a border. Before the Spanish invasion, there were villages along the Rio Grande, temporary village sites made up of Wamacs used by many Esto’k Gna clans. A village is not just a place, a village is a group of people that move together, says Christopher. The whole area, between the river and the ocean, was seen as a source of life and food, abundant with freshwater and saltwater ecosystems, and with important wildlife. Moreover, the delta was an important gathering and living area for many nomadic tribes and clans in this area, it was a place of union and communion and interrelatedness. Today, at the delta, there are fishermen on both sides of the river, fishermen throwing out their nets or lines and gathering fish to sustain themselves and their families.

Boca Chica beach, our working class beach, where RGV families meet, set up communal barbeque pits and share a meal. People still live very communally, adds Christopher, “this is the real magic of the Rio Grande Valley.” These are sacred ancestral sites for the Esto’k Gna people. Our ancestors live on through the air and water, and become our medicine, explains Juan Mancias. When we die our water evaporates and goes back into the earth. We are 70 percent of water, and this is how we are connected to our ancestors now.

Currently, these sacred sites are not accessible to the Esto’k Gna people. Space X closes the beach for a significant portion of the year, and Garcia Pasture, a sacred site of the Esto’k Gna, is considered private property seized by the Port of Brownsville so “if we try to go on this land, we would be arrested for trespassing, " says Christopher Basaldú.

Native peoples have been fighting to protect their sacred land for more than 500 years. There has been a systematic genocide of Native people in so called Texas to seize and steal sacred land. The anglos could not distinguish the natives from the indigenous and mixed mexicanos, and for survival native people would sometimes pass as Mexican. The pressure to proximate to whiteness in the social hierarchy, and the violent stripping of land and culture from indigenous people have created an ongoing de-indigenization process.

This is all part of a colonial project, explains Christopher Basaldú. Mexico is a European-colonizing nation, and the core of the nation-state is to be homogenous, it cannot have diversity. “La Patria” is a colonial project that systematized the racial caste system, creating blackness and brownness to have an exploitable labor base. The nation-state created “la patria” so that the white elite could have a cleaning lady.

“It is an extraction of land, and an extraction of our joy”

- Christopher Basaldú, Ph.D.

How to navigate this online exhibit

Our history is not easy to learn. It is painful, and also very important in understanding our current context on the South Texas border. This is an invitation to read and reflect, at your own pace, with the material but also to learn about yourself and your personal histories. We ask you to approach this exhibit as a learning tool and as a virtual library, one that you can come back to. Each section has citations to articles and books linked to the References section. Throughout the exhibit, we use words like colonization, settler imaginaries, and place myths. In this section, we define these terms to share a complete understanding of the frameworks we are using to explain the social and cultural landscape of the Rio Grande Valley Delta.

The Rio Grande Valley Delta

The Rio Grande Valley is really a Delta. The Rio Grande river flows into the Gulf of Mexico near Boca Chica Beach and Playa Bagdad. The river is literally shaping the landscape of the land between Mcallen/Reynosa to Brownsville/Matamoros. The Rio Grande Delta is home to a biodiverse ecosystem, one that we depend on. In the Lower Rio Grande Delta, in this tropical and arid place, also live descendants of the original peoples of this land, the Esto’k Gna, and families of agricultural workers who have worked the land and represent brown shades of beauty and resistance. We are a world’s majority area, with immigrants from Mexico, Central America, South America, India, the Middle East, and many other areas. The Esto’k Gna are the native people of this land who fight for its air, water, and sacredness each day.

In the Rio Grande Delta, we have a rare ecosystem that is precious to our health and our survival. Migratory birds show us that migration is natural and beautiful. Our wetlands are important resting points for migratory birds in their routes to their seasonal nesting spots, and provide shelter to many other endangered species. The militarized river can only release some of its tension into the gulf, as most of its waters do not reach the Gulf of Mexico. The water embraces our everyday worries and provides nourishment and joy. The montezuma trees, with their large roots have a reciprocal relationship with the river and our resacas. The subtropical climate provides a fresh breeze in the hottest seasons and our sabal palms provide shade and cooling for all species. Our community is friendly, it is a communal place, where networks exist and knowledge that we are social beings is part of el sentido comun. People speak with humility, and use humor to understand that life comes with difficulties. The lonely individualist life has wounded our souls and the American dream has proven false. Each person who lives here has their own story, and each of our stories make up the story of this place.

What do we mean by colonization?

¿Qué son Settler Imaginaries? And how do we dismantle them?

Texas public history education hero-rizes Anglo figures and upholds the myth that Mexicanos are bandits. In the present day, these false myths directly impact the social and political landscape. Anglo students who learn this history feel justified in their racist attitudes and in their support for racist government policies like the border wall and increased surveillance and policing of Mexicans. It also creates internalized self- hate for Mexicans who believe these false narratives and end up supporting these same racist laws. (Juan Carmona, interview, September 15, 2023)

As we address Texas hero-rizing Anglo figures, we return to Stephen F. Austin known as “the founder of Anglo-American Texas, where his hard work, dedication, and diplomacy enabled the Texas colonies to grow from lonely frontier outposts to an independent republic”

When we speak of the “settler imaginary” we are referencing the racist ideologies (a system of ideas), and worldviews that colonization violently imposed to institutionally justify the displacement and murder of indigenous peoples, the commodification of land and people, and the extraction of land for profit. We also are referring to the persistent systems of colonization that take form in imperialism, capitalism, and neoliberalism that continue to view land and people as profit. The vicious act of colonization is a worldview in action. This worldview is persistent today.

Through this virtual exhibition, we will examine the settler imaginary as the root of environmental destruction in the Rio Grande Valley Delta. In this exhibit we draw a parallel between the narrative of “there is nothing here” to the settler imaginary myth of land as “empty”. Finally, we show how these narratives and myths continue to be used by corporations like LNG and Space X, and complacent local governments to gain profit and power from the extraction and occupation of land in the Rio Grande Valley Delta. Below is an example of a settler imaginary myth.

Here, a former City of Brownsville District 2 City Commissioner responds to billionaire, Elon Musk, after he tweets that he will essentially establish a city on Boca Chica beach, a natural wildlife area once fully protected by the Texas Open Beaches Act. These statements are reflective of settler colonialism in many ways, namely the idea that you can settle in an area that has been inhabited by local people and wildlife for thousands of years, displace those who inhabit the land, and declare a new city to be built. The response by Tetreu, can be thought to be even more disturbing, but also works to affirm Elon Musk as a colonizer. The land waited many years for you to find it. In her worldview, he found this land, just like the European explorers found North and South America. This assumes that the land is empty and just waiting to be found and capitalized on. The land is there for the sole purpose of extraction.

Our identities are tied to this land. It is not empty, just as we are not empty. Land is not lonely, ecosystems thrive, and biodiversity depends on healthy ecosystems, which in turn provide an ideal habitat for humans. Our cultural and historical preservation is tied to this land.

Although colonization is a global issue, this exhibit focuses on the colonization of the Americas. Colonization is taught to us in school as “the discovery of the Americas”. This is an example of how history is erased and rewritten. The European “discovery” was a series of violent invasions, a system of stripping of lands, and the commodification and enslavement of brown and black people. North America was colonized by European empires, the English, the French, and the Spanish. The European colonization brought violence, genocide, and oppression to native peoples and established the slave trade in the Americas. Colonization sought land for profit, established an economic structure based on exploitation of the land, its resources, and enslaving brown and black people.

The land where we are currently settled on was stolen from native peoples. This is the main principle to understand and remember about the history of the Americas. The lands in Texas were “not lonely, nor empty, nor unoccupied,” they were fully inhabited by native peoples that embraced the Rio Grande as a natural, living system. Calling land “lonely”, “empty”, “unoccupied” is part of a settler imaginary that we are addressing through this exhibit.

Mashup image, source: National Geographic Online “Colonialism”

Through this exhibition we invite you to question the settler imaginary idea that “there is nothing here”. “There is nothing here” is not new, it has a long history. We argue that this same false narrative can also affect how we see ourselves and how we treat each other. If you were born and raised along the South Texas border, on either side of the river, we also invite you to reflect on how these narratives and myths shape how you view this place and the people here. How is this perception then connected to how you view yourself?

We need to dismantle settler imaginaries and the false narrative of there is nothing here to protect our abundant ecosystem and culture. We are working in the first step towards dismantling this harmful narrative, that is learning about our erased and untold history.

How did we get here? How can history explain the times we are living in? Scholar Monica Munoz, says that history bleeds into the present”. (7. The Injustice Never Leaves You) and this is especially true on the U.S Mexico border.

This exhibit offers history that was untold or erased from the ‘official’ South Texas history. It is the product of research by determined borderland scholars and it is essential for understanding our current life in the South Texas borderlands.

Education is a practice of freedom. Paulo Freire“La educación es una práctica de la libertad” – Paulo Freire

References:

7. The Injustice Never Leaves You, Monica Muñoz Martinez

8. Peons and Progressives https://philarchive.org/archive/WIMPAP

9. Inventing the Magic Valley (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230264017_Inventing_the_Magic_Valley_of_South_Texas_1905-1941

Links:

https://www.sabalpalmsanctuary.org/attractions/el-valle-the-rio-grande-delta/

https://favianna.com/artworks/migration-is-beautiful-2018

https://wildearthguardians.org/rivers/rivers-the-landscape/

https://www.tsl.texas.gov/treasures/giants/austin/austin-01.html

Image by Nansi Guevara

We are the Land, We the Esto’k Gna

We are all related.

Everything is connected. It’s all about relationships. Always.

We, original human beings of these lands never perceived the land as a dead thing, something to own or to possess. The land was never something to poison or destroy for the sake of money. The Land, the Earth was always and will always be our Mother, a relative; someone to honor and to respect. Someone who loves us.

We are all related.

That means that everything and everyone is related to everything and everyone else. This includes the land, or rather, the Place We come from, and every other living being and thing there in the Place we all share. Just as original people are connected to the land, their homeland, original indigenous peoples are connected to life and all that is living, together. Everything alive is also connected to Life itself, and that connection is through the land they live on, live with, live through,

Land itself, or our Mother Earth is alive with water, rivers, oceans, springs, resacas, and rain. The plants growing in the dirt are living through the water and light. We eat the plants, we eat the animals that eat the plants. Then We die. Our flesh feeds other living things. Our water and our bones return to the Land. Our spirits return to our ancestors. The Land, the Waters, the Air, the Light, the Stars; they are also the Ancestors. The deer, the bear, the herons, the turtles, the peyote; they are ancestors too. In our deep past, the animals, the plants, especially the medicinal ones and food plants taught us how to live well, and how to be better relatives to them and to others. Being a better relative, makes us better human beings.

Imagine! Our plant and animal relatives feed us, clothe us, shelter us. They give us life, literally. They are such good relatives. Our responsibility is to be good relatives to them too. We can say the same for the air, the water, and the land, our Mother.

This interwoven web of interconnected relationships are collective, not merely individual nor individualistic. This web of life ties us all together; people, places, ancestors, histories, future generations, plants, animals, all of whom just want to life and to be happy. This web binds us together to support us, and to teach us, remind us to support one another. We know and understand the interconnected Web of Life through our sacred stories, our sacred histories.

These stories teach us that we should support not just our human relatives, but all of our relatives. That includes the Land, the Water, the Air as well. The knowledge of how to live on the land and how to respect our relatives is carried in the stories and songs and practices we teach and pass down generation after generation, Our Lifeways. The web of songs and stories and knowledge binds our human community to the web of life.

Our ancestors were never “primitive”. They lived in ways that respected and reinforced non-abusive, non-extractive, non-exploitative relationships with our living relatives including the Land and other peoples. They knew the very complex ways of knowledge to survive and thrive in the different places and seasons throughout their sacred homelands. We, the Esto’k Gna, the “Human Beings” learned and taught how to live together respectfully throughout our sacred homelands, that we called Somi Sek. This knowledge lives here, on this land, in Somi Sek. We live here in Somi Sek with all our ancestors and living relatives. The more human we are, the more we honor and live our relationships in a good and healing way; in a life-giving way.

The colonizer invaded our homelands and teaches the ways of life-taking. Colonization kills, steals, destroys, and rips apart life and the Land. To harm, to abuse, to destroy. or to pollute these relatives betrays them through deep and extreme disrespect. In doing so, we become so dishonorable, we diminish our humanity. We deny our own responsibilities to our relatives through such horrible disrespect, and we destroy our own futures.

Our memories live through the love of those we leave behind. Then it lives again through the love given to the next generation. If we live our relationships in a life-giving way, then the next generation will do so as well, and so on and so on, as long as we remember how to give life. We do so through the relationships, the connections we collectively live with respect and reciprocity. The Land teaches us how to be truly human. We are born from the Land. We return to the Land. We are Esto’k Gna. We are the Land and the Land is us.

Ayema Payasel ( Give Life )

Written By: Christopher Basaldú, PhD

Colonization, Race, and the Caste System

All of North America was inhabited by native peoples before the invasion of European empires. (10. Harvest of Empire) In what is now known as Mexico, there are currently at least 68 indigenous languages that are spoken. The Spanish colonized the Aztec City of Tenochtitlan in 1519. Hernan Cortez invaded the Aztec empire and claimed it for the Spanish crown. The Spanish brought plague to the native peoples, they fought with iron swords and arms, and used surrounding forces of native groups that were dominated by the Aztecs. The Spanish claimed central Mexico and expanded their empire to what is now known as the Southwest, Texas, California, New Mexico, Arizona, and Colorado. (1. Mexico Profundo)

The Spanish set up a racial caste system, to not only justify the stolen lands, but also carry out an institutional domination of native land and peoples. The Spaniard was on top of the caste hierarchy, with native people and black enslaved people at the bottom. The mestizo classification was created, and became closer approximated to whiteness. Brown was inferior and white superior according to this system. (1. Mexico Profundo) This caste system withheld the right to own land, and made black and indigenous people the workers of the land through a system of haciendas. These labor groups became the campesinos and the agricultural workers of the land.

In the book, Mexico Profundo: Reclaiming a Civilization (1. Mexico Profundo) , the late Mexican writer and anthropologist, Bonfil Batalla, states that in Mexico, there are two civilizations that are parallel, not fused, but rather live in constant conflict . Batalla speaks of these two civilizations and called them, Mexico Imaginario, made up of those who impose westernization, and Mexico Profundo, those who are rooted in Mesoamerican ways of life and resist. The country is mostly run by the Mexico imaginario, one who looks at progress as westernization.

“What has been proposed as a national culture at different moments in Mexican history may be understood as a permanent aspiration to stop being what we are… The task of constructing a national culture consists of imposing a distant, foreign model, which in itself will eliminate cultural diversity and achieve unity through the suppression of what already exists. In this way of thinking about things, the majority of Mexicans have a future only on the condition that they stop being themselves. Its origin lay in the installation of the colonial regime almost five hundred years ago.”

- Bonfil Batalla, Mexico Profundo (1) p. 63

References:

1. Mexico Profundo, Guillermo Bonfil Batalla

10. Harvest of Empire, Juan Gonzalez

Links:

1521: Hernan Cortes violently claimed Tenochtitlan as the new capital of New Spain, (Today’s, Mexico City). Mexico City became the headquarters for colonization of more territory in modern day Mexico. The Spaniards determined territory that was of interest to them based on proximity to the capital and where they possessed precious minerals, silver or gold, that were deemed valuable to the Spanish. The area now known as the lower Rio Grande Valley Delta was too arid to be considered as desirable for settlement.

1590: Spanish exploitation of land and people in the lower Rio Grande Valley began. A Spanish soldier and viceroy to the Spanish crown, Carvajal took thousands of native people and sold them to mining settlements as slaves. The natives resisted and lost trust for the Spanish. (Juan Carmona, interview, September 15, 2023)

1620: The Mayflower colonizers violently displaced and murdered native peoples and established Plymouth colony. The Wampanoag are the original peoples of that land and it had been widely known as turtle island for 15,000 years.

1700s: The British colonial settlements were formed into the 13 colonies.

1749-1750: Colonizer Jose de Escandon was sent by the Spanish crown to colonize the area now known as the Rio Grande Valley Delta, calling this land Nuevo Santader.

1750 and 1821: Spanish Crown Land Grants

Land grants were portions of land granted by the Spanish Crown to Spanish colonists after colonization.

In 1787 the Spanish surveyed the land that is now known as the south Texas border and granted porciones, long narrow lots of land, along the Rio Grande River, which ensured water access to each.

The bourbon reforms of 1767 were aimed at profiting even more from the exploitation of land, defining land as private, and as individual property. These reforms also established ports that could only trade goods with Spain and established state monopolies and more political control of the territory. (4. Building the Borderlands)

1776: 13 colonies become independent from Britain after the U.S War of Independence

1803: The Louisiana Purchase happened, and salvation for westward expansion began. Manifest Destiny was “the idea that the United States is destined by God, to expand its dominion and spread democracy and capitalism across the entire North American continent.” Tribes across the northern United States were violently killed and displaced further west.

1820: The Spanish government passed a policy to open Texas to outside settlers from the American frontier in order to stop Native American defenses of their own land. More anglo settlers in Texas created more racialized conflict between Mexicanos and Anglos.

One of the land grants was allotted to Moses Austin in 1821, father of Stephen F. Austin, in exchange for bringing 300 more U.S colonists to the area.

1821: Mexico became independent from Spain in 1821. The population of Texas was mostly Native American. Mexico began to restrict slavery until it was abolished in 1829, and Anglo Texans were not happy.

1829: Mexico abolished Slavery

1836 - 1845: Texas became an independent country, kept slavery legal, and in its Constitution, disqualified African Americans, Indians, and Mexicanos from having citizenship. Section 10 read “All persons, (Africans, the descendants of Africans, and Indians excepted,) who were residing in Texas on the day of the Declaration of Independence, shall be considered citizens of the Republic, and entitled to all the privileges of such." Dark skinned Mexicanos were excluded from citizenship and would be categorized as African or Indian. (Juan Carmona, interview, September 15, 2023)

1846: The US unofficially claims Texas. Mexico did not want to lose the southwest and so the Mexican American War happened.

1848: The treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed in 1848, and Texas became a part of the US, setting the boundary and border as the Rio Grande River.

1861-1865: The Civil War started to industrialize the north. The South fought to keep the institution of the slavery. Cotton was shipped from Mexico through Brownsville, Texas, avoiding the Union blockade of Confederate ports. Charles Stillman, owner of a steamboat company, smuggled cotton and defended the Institution of slavery. (10. Harvest of Empire)

1898: The U.S claims to ally with Cuba against the Spanish to protect its own economic investments and interests in Cuba. (10. Harvest of Empire) The Spanish American War set the ground for U.S Imperial invasion and annexation of Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Guam.

*20th Century U.S Invasions and Interventions will be discussed in Section 12: Our History Connects Us to Now

References:

4. Building the Borderlands, Casey Walsh

10. Harvest of Empire, Juan Gonzalez

Links:

https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/constitutions/republic-texas-1836/general-provisions

Downloads:

https://decolonialatlas.files.wordpress.com/2023/10/turtle-island-decolonized-map-with-index.png

Timeline of colonial invasions

Racial Scripts & Policing

Bandidos. Local businessmen playact as drunken Mexicans, Brownsville, Texas, Charro Days, 1942, Library of Congress Archives

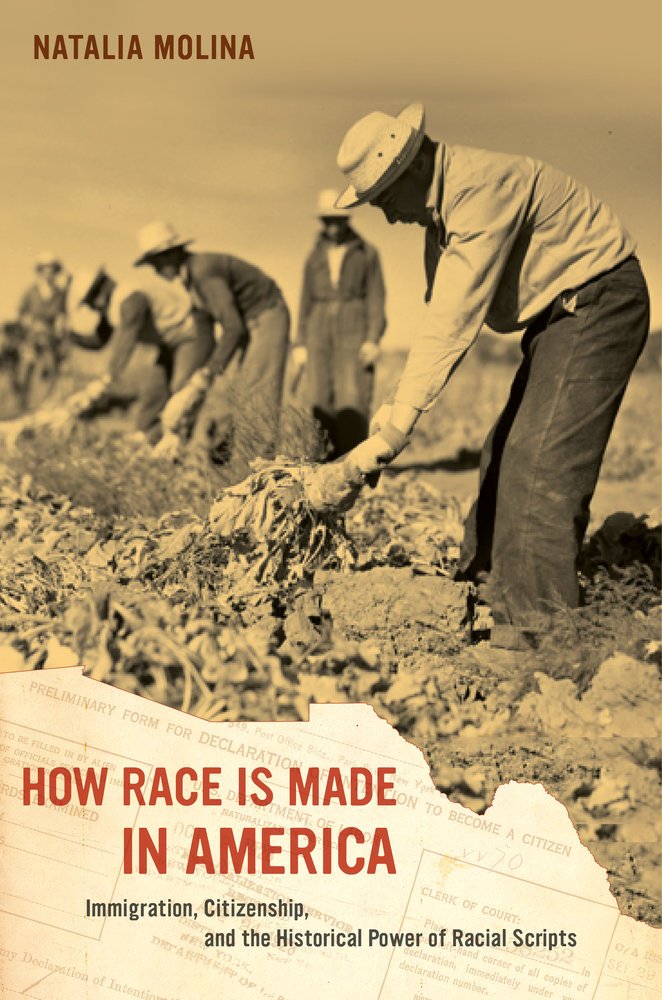

The racial caste system of both imperial nations dominated the lower Rio Grande Valley. In her book, (6) How Race is Made in America, Natalia Molina, describes repetitive racial narratives that are used to marginalize groups as racial scripts. These racial scripts have been used across time, and recycled across racial groups in the United States. “The notion that Mexicans, like blacks, were a population ready to spiral out of control was a popular racial script for portraying Mexicans as unsuitable newcomers.” Is used to deny the right to immigration for Mexicans. Molina writes “politicians and everyday citizens argued that, like slaves, the Mexican population would increase at unprecedented rates and create a multitude of problems.” The photo above was taken in Brownsville during the Charro Days Celebrations and it shows a group that appears to be white men upholding the racial script of Mexicanos as “bandidos”. Bandidos was a racial script used to justify state sanctioned violence, criminalization, and deportation of Mexicans.

Richard L. Copley, I am a man, 1968, photographic print

“Slavery was a political economic system designed to extract the greatest profits for whites. Regarding blacks as racially inferior helped whites justify using them as slaves. The low wage labor Mexicans engaged in in the Southwest was in no way comparable to slavery: the thread that runs through both political economies, however, once again places an emphasis on the profits for those at the top of the power structure while disregarding those doing the labor… Thus comparing Mexicans to slaves was not just a racial comparison but was fundamentally about how to continue to fuel the political economy while maintaining a racial hierarchy.”

- Natalia Molina, 6, How Race is Made in America

Spider Martin, Rev. Hosea Williams, John Lewis, and others in the March for Voting Rights to Montgomery confronted by Alabama State Troopers, Selma Alabama, 1965, Photograph, 13 x 19.5 inches, James “Spider” Martin photographic archive, Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin

Photograph, Jonathan Bachman, protester Leshia Evans being arrested in Baton Rouge, 2016

References:

6. How Race is Made in America, Natalia Molina

From Ranching to Mass Industrial Agriculture

Most of what today is known as the Rio Grande Valley Delta was home to nomadic native tribes before it became commodified into land grants and private property. Ranching became the main economic system, with more anglo settlement and accumulation of wealth, the economic base of this area became mass industrial agriculture in the early 20th century. In her book, (4) Building the Borderlands, Casey Walsh, explains how water management transformed the river delta region into a center for agriculture commerce based on irrigation and the shifting of land. (4. Building the Borderlands)

Cotton weighing near Brownsville, Texas, photographer Dorothea Lange, 1936 Aug.

In 1904, wealthy landowners worked to bring a railroad line to South Texas. This was thought to raise land values, which would create more profit from land sales and farming as the railroad could transport produce further north. (8. Peons and Progressives). On the opposite side, the Mexicanos suffered, as they could not afford the rising taxes caused by the increase in valuations on their property. This created a significant shift in the RGV’s economy from ranching and grazing to mass industrial agriculture.

(The American Rio Grande Land and Irrigation Company) Margaret H. McAllen Memorial Archives, Museum of South Texas History, Edinburg, TX.

Cotton is a crop linked to a deeply violent history. Enslaved black people produced most of the cotton in the cotton belt of the United States between 1715-1865. During the U.S Civil War between 1861-1865, the southern confederate states called for secession in order to maintain the institution of slavery in the South. The union blockade prevented the confederate states from trading any of their goods. Northern Mexico then became a cotton producing region with cotton being a very profitable commercial crop. Merchant capitalists from Monterrey profited highly from cotton during the US civil war and looked to make investments in textile industries in the early twentieth century. (4. Building the Borderlands) *See Section 12: Our History Connects Us to Now

Monterrey, Mexico became a center of textile industry, which created more fiber demand and made the Laguna region of Coahuila and Durango into a center of commercial cotton agriculture. This led to plans to create irrigated cotton zones in other regions of northern Mexico, including on the border in Matamoros. The textile industry (4. Building the Borderlands) required outside investments, and the open door policy of the Porfiriato to U.S investments helped create the mass industrial agriculture in northern Mexico.

Cotton was profitable because of exploitation of labor. Cotton production demanded a large amount of labor for specific moments in the production process, one being during harvest, la pizca. (4. Building the Borderlands) This created a temporary worker exploitative system. Eventuales stayed in the area and looked for other part time work in other industries, such as mine or railroads. Large numbers of underemployed migrant workers and cheap labor demands led to large mobilization of agricultural workers. (4. Building the Borderlands) The labor demands of cotton production mobilized groups of laborers to fight for their rights and gave rise to the start of the Mexican Revolution in the borderlands. *See Section 11: Resistance

References:

4. Building the Borderlands, Casey Walsh

8. Peons and Progressives,

Free download: https://philarchive.org/archive/WIMPAP

The Magic Valley Boosters

& Settler Place Myths

This land has been through many layers of colonization, starting with the stealing of land from the Native American Tribes here. The change from a ranching society to one based on mass agriculture added another coat of colonial extraction. One that brought loss of land and less economic opportunities for middle to lower class ranchers and vaqueros. (Juan Carmona, interview, September 15, 2023) They had to seek work in the agricultural sector, and work on the lands that some of them once owned. These labor jobs did not pay the same and required mass amounts of labor. The shift to mass agriculture was led by anglo merchants who saw a business venture on the lands of the Rio Grande Valley Delta. This led to the building of mass irrigation systems and an advertising campaign to lure more anglos from the north to invest in these lands, with the promise of cheap Mexican labor at hand. (8. Peons and Progressives) This campaign was called the Magic Valley. Mexican American Studies teacher at Donna High School, Juan P. Carmona adds “This economic shift also created resentment in the Mexican community and held back generations from becoming prosperous members of society. This is also because the Texas Rangers *see section 10: Violence of the South Texas Mexico Border* would ally with local anglo merchants to violently displace and steal Mexican land and coerce Mexicanos into selling their land. Those who reside in the Valley today are still playing catch up, from all that was taken from them.” (Juan Carmona, interview, September 15, 2023)

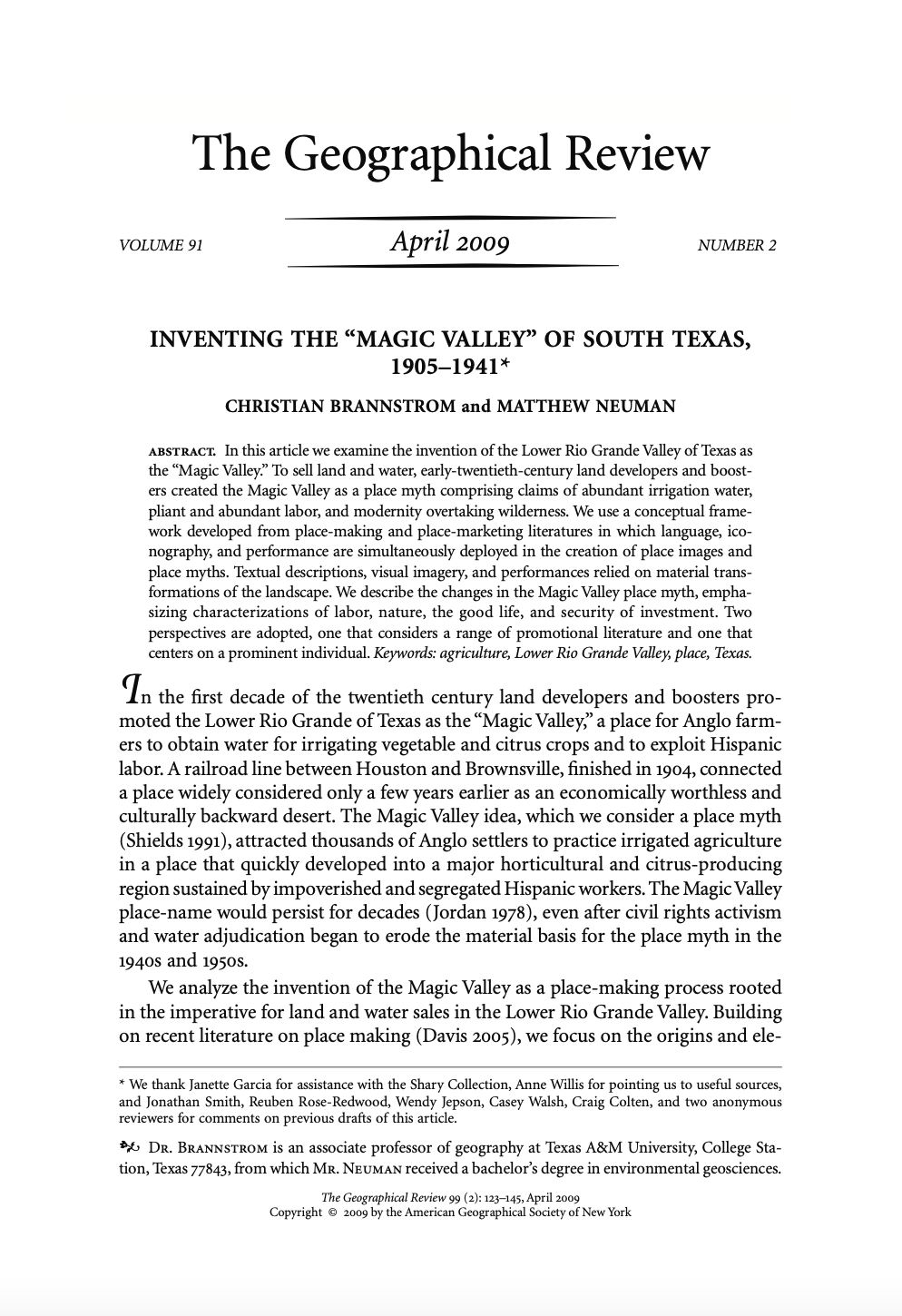

In the article, inventing the Magic Valley, scholars Christian Brannstrom and Matthew Neuman talk about the imposition of place myths in the Rio Grande Valley. In this case, a myth is something that is not true. A place myth can be described as an untrue narrative imposed onto a place. In the examples below, you see how images and advertisements created a myth of the Rio Grande Valley Delta.

The City of Palms, 1927, Rio Grande Valley Promotional Literature Collection, Box 1. The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley Library Archives and Special Collections.

“In the magazine In Rio Grande Valley Paradise, Sharyland the cover presented the viewer with the imagined future of the area should it come under the productive and disciplined organization of “progressive” and “thinking men.” The illustration was an imagined aerial view of orderly rows and columns of crops and citrus trees, evoking notions of productivity, order, security, regularity, and discipline over the natural forces of land, water, and labor. No longer was the land littered with masses of dry shrub and cactus and randomly dotted with clusters of mud huts but rather the gridded profit-bearing trees and crops were regularly intersected by paved roads and planned infrastructure. These grids provided clear boundaries for property rights, provided efficient controlled channels through which capital could travel, and through social institutions, provided for the proper racial and class relationships.” (8. Peons and Progressives, p.15)

In Peons and Progressives, the authors describe that the racialization of Mexicans creates an image of a place that is profitable for the anglo landowner, keeps Mexicans subservient and the source of labor, and provides comfort and security for the new anglo settlers. The Texas Rangers often worked alongside wealthy investors and landowners, to instill terror into Mexicanos and keep them as the cheap labor promised in the advertisements. Through analyzing the promotional materials of early 20th century boosters, we also see the racialization of the Mexican for the continual colonization (exploitation of land and people as labor) for profit. Examining these booster materials is important in understanding that current racial narratives in the Rio Grande Valley Delta have a historical precedent.

American Rio Grande Land and Irrigation Company, See Texas First, 1930, Rio Grande Valley Promotional Literature Collection, Box 1. Photo courtesy of The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley Archives and Special Collections.

The Mexican was called a peon, a low skill labor with an accompanying text found next to this image of a Mexican labor and his donkey, as a “gleaner”. This word refers to gathering in small portions, specific to gathering what is left after big harvests. Similarly as how natives were portrayed as uncivilized for being hunters and gatherers, and not having a system of agriculture. (8. Peons and Progressives) These images are part of the white imaginary, that created these perpetual place myths to denigrate, vilify, and belittle the local indigenous people.

(Home Sweet Home) Margaret H, McAllen Memorial Archives, Museum of South Texas History, Edinburg, TX.

Another example is how the promotional materials reference “Jacales”, as clusters not homes. (8, Peons and Progressives) These Mexican and Native American homes were made out of materials you would normally find in the landscape, sticks, mud, and grasses. Mexicans and Natives were seen as uncivilized, because they “failed” to tame the land and water for the “progress of civilization”. Irrigation was seen as progressive, providing the farmer with water, “whenever he needed it.” (8. Peons and Progressives) *See Section 7: Racial Scripts and Policing and how these jacales were mocked in Brownsville during Charro days.

References:

8. Peons and Progressives

Free Download https://philarchive.org/archive/WIMPAP

9. Inventing the Magic Valley

Free Download https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230264017_Inventing_the_Magic_Valley_of_South_Texas_1905-1941

Links:

Violence on the South Texas Mexico border

Land equaled investments and high profits for Magic Valley boosters, which meant that investors used the power of the state, surfaced a violent wave of policing justified through racial narratives to protect their investments. It has been documented that between 1910- 1920, thousands of Mexicanos were violently killed in South Texas. Today, scholars call these events, La Matanza. (Refusing to Forget Project)

Historical Marker between San Benito, Texas and Brownsville, Texas. Photo taken by Nansi Guevara

In the Lower Rio Grande Valley, at the southern tip of the state, large numbers of white Americans moved to the region for the first time, so many that the population nearly doubled within just a few years. Rising land values, increased property tax bills, and land title disputes worked to strip many ethnic Mexicans of their land. …As a Laredo newspaper observed in 1910, “The lands which mainly belonged to Mexicans passed to the hands of Americans . . . the old proprietors work as laborers on the same lands that used to belong to them.”

The newcomer farmers showed little or no respect for the enduring economic, cultural, and political power held by ethnic Mexicans in South Texas. These northerners increasingly turned to the tactics of segregation and marginalization, supported by statewide measures such as the poll tax and whites-only policies. These institutional policies are known as Juan Crow.

The turbulence of the Mexican Revolution (1910-20) exacerbated an already tense situation. Over the course of the decade, nearly a tenth of the Mexican population would perish and another tenth would flee to the United States, setting into motion a pattern of migration that endures a century later.

Robert Runyon, 1915, Texas Rangers pose on a South Texas ranch in 1915 after one of their notorious "bandit raids." The Center for American History, the University of Texas at Austin.

The Texas Rangers

The Texas Rangers were founded to expand the white man’s frontier even further west and protect white settlers from natives. The untold history of the Rangers is the cruel violence, brutal policing, and mass killings they incited on the South Texas border. The Texas Rangers were sent down to the border to pacify the border.

In the Texas Monthly podcast, Juan Herrera examines the image of the Texas Ranger, and the historical violence that still struggles to be acknowledged in history and by the force today. (Texas Monthly podcast)

Trinidad Gonzales, a current professor of Mexican American Studies at South Texas College and co-founder of the Refusing to Forget Project, remembers his family speaking of the Texas Rangers, only that they called them Los Rinches. He recalls his seventh grade history class in 1982:

Trinidad Gonzales: The textbook about the Texas Rangers was: “Texas Rangers good; Mexicans, Indians, bad. They helped settle the frontier and pacified and dealt with . . . So you’re reading that as a Mexicano and reading about the Texas Rangers, and as a twelve-, thirteen-year-old, you’re going through this psychological tension of like, “Okay, my family has told me these stories about los rinches and how they killed my great-grandfather and his father.” But I’m reading it in the official state textbook of Texas saying Mexicans are bad. So that poses a question to Trini at that age, it’s like, “Are my family lying to me? Or maybe my ancestors were bad? How do I deal with this? How do I reconcile what I’m being told at home and what I’m reading in the textbook?” And my teacher was Mr. Garza. And of course, he’s mimicking what the textbook says, “Well, the Rangers were good. The Mexicans were bad. They were bad Mexicans.” And of course I’m not participating because I don’t know how to participate in that conversation. He goes, “Well, don’t believe everything you read in the textbooks. The old people call them los rinches.” It was the first time I ever heard an educator tell me that, or a teacher tell me that. And there was such an affirmation to like, “Oh, okay. My family’s not crazy. I haven’t been lied to, right?”

- White Hats Podcast

Links:

https://refusingtoforget.org/the-history/

Texas Monthly podcast White Hats Podcast

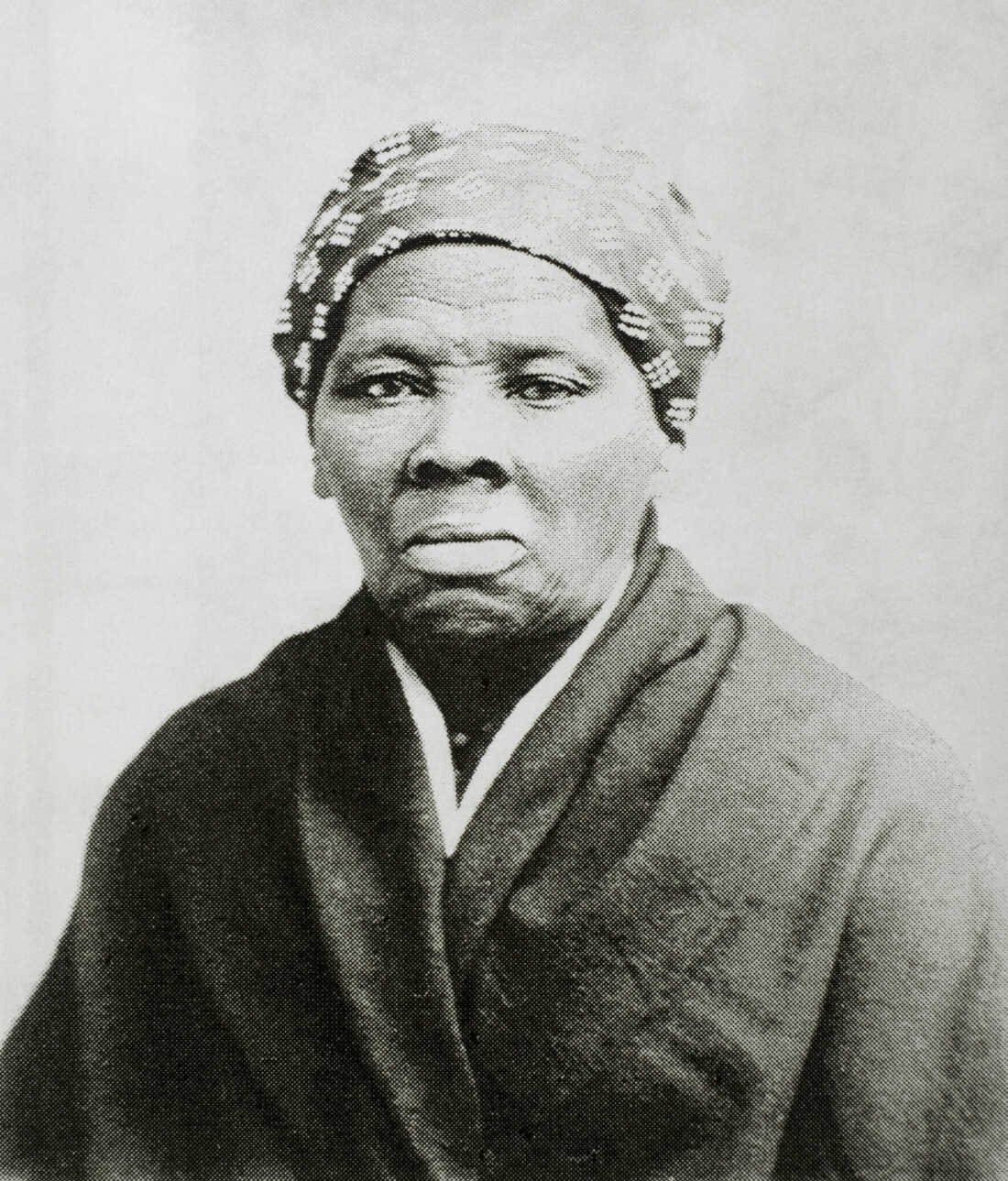

Harriet Tubman, Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images

Mexico outlawed the institution of slavery decades before it was abolished in the United States. Abolitionist and activist, Harriet Tubman, escaped slavery by using networks of abolition activists and safe houses known as the Underground Railroad. Harriet Tubman made many trips to the south to help other enslaved black people escape including her own family and friends. Tensions grew between the northern and southern states before the civil war, which led to a passing of a group of laws known as the “Fugitive Slave Acts”. This gave so-called “slave catchers” the legislative right to enter the north and retrieve “alleged” runaway slaves. (Juan Carmona, interview, September 15, 2023) Fearful of capture, formerly enslaved people looked to Mexico as refuge. Afro-Mexican second president of Mexico, Vicente Guerrero abolished the institution of slavery in 1829, and it became a law in 1837. At this time, in what is now Texas, anglo settlers claimed to be oppressed by Mexico, who did not align with their own “democratic” ideals. These “democratic ideals” for Anglo Texans meant the “right to protect” the institution of slavery.

Vicente Guerrero, A half-length, posthumous portrait by Anacleto Escutia (1850), Museo Nacional de Historia.

Enslaved people in Texas had a possibility of escaping through the south, through the Rio Grande Valley to Mexico. The terrain was tough and dangerous to navigate, the South Texas brush that today still threatens the lives of migrants today. According to Nosotrxs Por el Valle, a group of RGV historians, The Webbers and the Jacksons were two mixed race families who both owned ranchers along the Rio Grande River and operated ferries, which they would use to safely cross escaped enslaved peoples into safety in Mexico. (Juan Carmona, interview, September 15, 2023)

The Cortina Wars

William H. Emory, (Archival Photograph by Mr. Sean Linehan, NOS, NGS) - "United States and Mexican Boundary Survey. Report of William H. Emory ...." Washington. 1857.

After 1848, the area known as the Rio Grande Valley Delta became part of the United States. The new anglo investors allied with local authorities and manipulated the political system to lay the grounds for anglo stripping of lands and accumulation of wealth. The Texas Rangers intimidated Mexican landowners to sell, often killing men, and making their widows surrender their lands. Juan Cortina’s family at the time owned much of the land in what is now Brownsville, Texas. Juan Cortina shot the city Marshall for violently mistreating a servant of his mothers. In 1859, Cortina along with 70 men occupied the town of Brownsville, resisting Anglo dominance and Texas Ranger violence. This is now known as the first Cortina war with the second following in 1861. Cortina escaped to the Mexican side of the border, and the Civil War began, which made it easier for him to evade capture. Cortinas would begin to operate from the Mexican side, fighting with the Union against Confederate soldiers. Porfirio Diaz imprisoned Cortinas and he died in prison in Mexico in 1894. Dictator Diaz also wanted to pacify the border, cooperating with the U.S, any men that would flee to Mexico would be returned to U.S soil through the Porfiriato dictatorship. (see Wikipedia, Cortina Wars)

El Plan de San Diego

In 1915, Bacilio Ramos traveled from San Diego to South Texas, where he was captured and arrested by the Texas Rangers for a document he would be holding close to his guard. The document was a manifesto, el Plan de San Diego. (Juan Carmona, interview, September 15, 2023)

El Plan de San Diego called for a “Liberating Army for Races & Peoples” to kill every white male over sixteen years old and to seize Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and California. The first lands to be seized were to be given to African Americans and Indigenous communities to build for themselves independent nations– sanctuaries–free of Anglo-American domination.

-Kelly Lytle Hernández, (3. Bad Mexicans, P. 298)

That same year, groups of Mexicans and Mexican Americans started killing white men under the name of El Plan de San Diego. According to Kelly Lytle Herández, author of Bad Mexicans, El Plan de San Diego was one of the largest and deadliest uprising against white settler supremacy in US History. And it is not very well known and of course never part of our history classes in South Texas. (3. Bad Mexicans)

In retaliation the U.S army sent 4,000 troops into South Texas, and together with the Texas Rangers committed mass murder of Mexicans and Mexican Americans, this would be known by scholars as La Matanza. These mass killings and lynchings would send ripples of terror into Mexican and Mexican American families in South Texas.

*See Violence on the South Texas Border

The Magonistas y el Partido Liberado de México

1916, Ricardo and Enrique Flores Magón at the Los Angeles County Jail.

En la fotografía aparecen: Federico Pérez Fernández, Santiago de la Hoz, Manuel Sarabia, Benjamín Millán, Evaristo Guillén, Gabriel Pérez Fernández, Juan Sarabia, Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama, Rosalío Bustamante, Tomás Sarabia y Ricardo y Enrique Flores Magón. Mexico City, 1903.

In her book, Bad Mexicans (3), Kelly Lytle Hernandez states the important role south Texas had in the shaping of the United States. She writes that the violence on the south Texas border, the rise of imperialism, and white supremacy at the turn of the 20th century led to an uprising that sparked the Mexican Revolution.

In Mexico, Porfirio Diaz, the once hero of the Battle of Puebla (1862), rose to power as a dictator. Bypassing the Mexican Constitution law of limiting presidential terms in power, Porfirio Diaz stayed as president for 30 years. This period is known in history as the Porfiriato. (3, Bad Mexicans)

During the Porfiriato, Diaz used “rurales”, a rural police force, to violently appease and control the Mexican resistance. The “rurales” were responsible for committing mass violence in small rural areas and violently killed and displaced Yaqui people in Mexico.

Porfirio Diaz opened the doors for the US. Investors in Mexico that together with the railroad connection to the United States from central Mexico flooded Mexico with US dollars. (3, Bad Mexicans) U.S. investors purchased about 130 million acres, nearly a quarter of the Mexican landbase, said Kelly Lytle Hernandez in a Democracy Now interview.

“US investors come to dominate key Mexican industries, like railroad, oil, mining, and more. And it is that invasion of US dollars and also European dollars that displaces millions of mexican peasants, community folks, rural folks, indigenous populations. They become displaced, become wage workers and then they begin to migrate into the United States in search of work. This is the beginning of mass labor migration between the US and Mexico.” - Kelly Lytle Hernanez, Democracy Now Interview

Ricardo Flores Magon and his brothers were journalists in Mexico, and published a newspaper called Regeneración, in which they called Porfirio Diaz a dictator and said that Mexicans became the servants of foreigners. At the time, there was no public denunciation of the Diaz regime. Diaz had Flores Magon arrested multiple times and imprisoned him in one of the harshest prisons in Mexico. A gag, prejudiced rule was issued, which restricted any free speech against the Diaz regime, so Flores Magon and his group were obligated to look for a safer location and crossed the US Mexico border through Laredo, Texas.

In the United States, Flores Magon and his group of socialists/anarchists established el Partido Liberado de México and built a small army. They raided Mexico four times and were able to destabilize the Diaz regime. The US reacted as it wanted to protect their economic investments. The Magonistas and PLM army incited the outbreak of the 1910 Mexican Revolution. (3, Bad Mexicans)

One of the insurgency leaders of El Plan de San Diego was Ancieto Pizaña, who was also a part of the Partido de Liberado de México. Pizaña met Ricardo Flores Magon in Laredo, Texas in 1904. The parallels seen between the Diaz regime rurales and the Texas Ranger and anglo violence created more collective resistance. (3, Bad Mexicans)

In 1916, both Flores Magon brothers were convicted and imprisoned for publishing their support of the Plan de San Diego and violating the Espionage Act. U.S Authorities viewed Ricardo Flores Magon and his anarchist and revolutionary ideas as a threat. Ricardo Flores Magon died in prison and his brother, Enrique Flores Magon went on to document and archive his story, as one of the key people that incited the Mexican Revolution. (3, Bad Mexicans)

JT Canales

In 1919, José Tomás Canales, the only Mexican-American legislator in Texas, and State Representative for Brownsville, was dismayed by the violence happening in his district. He suspected there was an abuse of state power and that the Texas Rangers were acting with impunity. (White Hats Podcast) Canales filed a request for witness testimonies and hearings. His intention was to restructure the force and prevent any more unlawful violence. This was the first time these mass murders were discussed publicly. Canales used his state position to bring accountability to the force in order to reform it. The Texas Legislature hearings heard the testimonies of more than 90 people, that detailed evidence of killings, torture, and harassment at the hands of Texas Rangers. (White Hats Podcast) *See Section 10: Violence on the South Texas Mexico Border

The Texas Ranger fired a counterattack and claimed that its force was necessary within an unstable and violent South Texas. The lawyers who represented the Texas Rangers claimed that Mexicanos were inherently violent and in order to control these populations, the Texas Rangers were obligated to use force. (White Hats Podcast)

The transcripts of the Canales hearings were sealed for 50 years, since the Canales investigation had been closed. In 1975, James Sandos, uncovered the transcripts and the archivist told him that the last person that had seen the transcripts was Walter Prescott Webb in 1919. Walter Prescott Webb shortly after went on to write a history of the Texas Rangers, called The Texas Rangers: A Century of Frontier Defense, one where he made the Texas Rangers, and his friend Hammer into heroes and legends. Hollywood then made a movie based on his book called The Texas Rangers. Monica Muñoz Martinez, Mexican American History scholar and founding member of Refusing to Forget, says that Webb knew about the violence. She adds, he is not telling the story from the point of view of people who were massacred. He’s telling it from the point of view of the Texas Rangers. And so he’s justifying their actions. (White Hats Podcast)

Jovita Idar

Helaine Victoria Press, Jovita Idar (1885-1946) [postcard], 1986. W075_029, Feminist Postcard Collection, Archives for Research on Women and Gender. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University.

Jovita Idar was a feminist journalist based in Laredo, Texas. Her family’s weekly newspaper, La Cronica, was the only publication documenting the lynchings and violence in the region. (3, Bad Mexicans) Jovita’s father had taught her that as a family they had an obligation to “fight for the Mexican people.” (3, Bad Mexicans)

Jovita and her family wrote extensively about Texas Ranger violence and the Canales hearings. Their newspaper also covered the threats and discrimination that JT. Canales faced during and after the hearings at the Texas capital.

In 1914 in Laredo, Jovita Idar bravely stood in front of the entrance of El Progreso press when a group of Texas Rangers tried to enter with the intention of destroying the printing press. This happened after the newspaper wrote a criticism of President Woodrow Wilson's order to send U.S military troops to the U.S Mexico border in order to pacify the “bandit violence” . The Texas Rangers came back the next day and before she arrived, they destroyed the press and arrested a few of the workers. The Progreso Press did not stop. They continued publishing many front page news articles, including following the case on Gregorio Cortez.

The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez: Corridos as a form of resistance

Image courtesy of the Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

In 1901, on a ranch west of San Antonio, County Sheriff William “Brack” Morris wrongfully accused Gregorio Cortez of horse theft. Morris led the Rinches on a humiliating manhunt across the borderlands. (3, Bad Mexicans) In the attempt to arrest Cortez, Sheriff Morris killed his brother and Gregorio shot the Sheriff. After that, Gregorio had to flee to save his own life.

For many Mexican Americans across Texas, who knew of the histories of oppression and violence and racism, Gregorio Cortez became a folk hero. Mexican Migrant workers followed the case of Gregorio Cortez through hearing the corrido, imagining this folk hero as someone who fought off a more powerful enemy. (3, Bad Mexicans) Monica Muñoz Martinez of Refusing to Forget and author of The Injustice Never Leaves You (7, The Injustice Never Leaves You), says, corridos were the Mexicanos version of history, a story of survival. (White Hats Podcast)

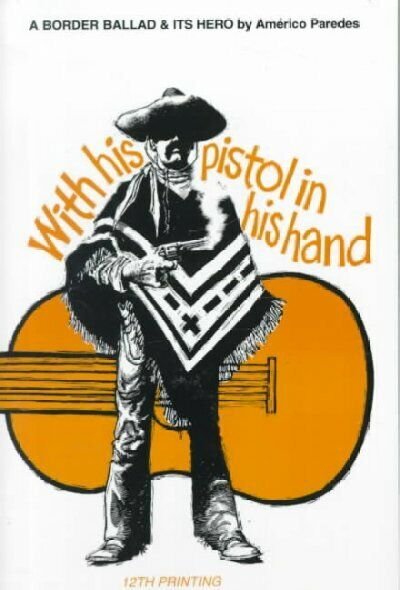

Americo Paredes’s book, With a Pistol in his hand chronicles the life of Gregorio Cortez, was a direct challenge to Ranger mythology. (12, With a Pistol in His Hand) It presents the significance of the corrido as a form of resistance. Americo Paredes was born and raised in Brownsville, Texas. His writings helped inspire the Chicano movement. (White Hats Podcast)

References:

White Hats Podcast Texas Monthly podcast

3. Bad Mexicans, Kelly Lytle Hernández

7. The Injustice Never Leaves You, Monica Muñoz Martinez

12. With a Pistol in His Hand, Américo Paredes

Links:

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p1535.html

Resistance

There is always resistance to violence. South Texas experienced deep violence as an area open for dispute by colonial imperial powers, as an area salivated by the U.S empire and the doctrine of Manifest Destiny, the brief independence of Texas who wanted to uphold the institution of slavery, and the institutions of the Texas Rangers and the Border Patrol who were formed to “pacify” Mexicano rebels and “bandits”. The following sections are not the only historical accounts of resistance, but each will give you an introduction into important events of resistance in South Texas.

The Underground Railroad

our history connects us to now

A Spanish propaganda drawing published in La Campana de Gràcia (1896) by Manuel Moliné criticizing U.S. behavior regarding Cuba. Upper text (in old Catalan) reads: "Uncle Sam's craving", and below: "To keep the island so it won't get lost".

If Latin America had not been raped and pillaged by U.S. capitalism since its independence, millions of desperate workers would not now be coming here in such numbers to reclaim a share of that wealth; and if the United States is today the world’s richest nation, it is in part because of the sweat and blood of the copper workers of Chile, the tine miners of Bolivia, the fruit pickers of Guatemala and Honduras, the cane cutters of Cuba, the oil workers of Venezuela and Mexico, the pharmaceutical workers of Puerto Rico, the ranch hands of Costa Rica and Argentina, the West Indians who died building the Panama Canal, and the Panamanians who maintained it. (10. Harvest of Empire)

3. Imperialist neoliberal and free trade policies continue to exploit people and the earth

In the mid twentieth century, the U.S started moving large manufacturing enterprises (maquiladoras) to other countries, especially in Latin America that began the U.S project of “free trade” policies. The U.S tentacles worked on agreements with neighboring nations to lower their high tariffs, then closing domestic factories in order to open them in Latin America. (10. Harvest of Empire) Beginning in 1965, manufacturing shifted to Mexico and maquiladora factories started to be built along the Mexican side of the US/MX border. U.S goods were produced way cheaper in Mexico and U.S. corporations’ could evade paying higher wages to domestic labor workers, taxes, and environmental laws as these factories were located on foreign soil, regardless if they were just a few hundred yards away from the US Mexico Border. The maquiladora jobs sparked mass internal migration in Mexico toward the north. People moved north from rural towns to the maquila factories that would primarily hire women. Men who joined these women as their partners, often could not find work, and would have to migrate further north into the United States. As a result of these migrations, the population in many border towns like Tijuana, Nuevo Laredo, or Matamoros grew exponentially creating a challenge for these cities that did not have the infrastructure to house that large population. In addition, these factories created contamination, and polluted the area and further polluted the Rio Grande River. (10. Harvest of Empire)

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) to establish a free-trade zone in North America was signed in 1992 by Canada, Mexico, and the United States and took effect on Jan. 1, 1994. NAFTA immediately lifted tariffs on the majority of goods produced by these nations. At that point, Mexico was in the middle of an economic crisis that dramatically devalued the peso. The economic crisis was the effect of President Carlos Salinas’s open-door policy towards U.S investments. (Harvest of Empire) On the same day that NAFTA took effect, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) launched a protest uprising in the state of Chiapas, Mexico. The uprising gathered international attention, and 100,000 people protested in Mexico City. NAFTA policies affected millions of Mexican rural and poor corn agricultural workers, an important dietary food at the heart of Mexican culture. With the reduction of the U.S./Mexican import/export tariffs meant small farmers were affected and could not compete with the mechanized mass agricultural system of the United States. As a result of NAFTA, the US cheaper, pest-resistant, genetically modified (GMO) corn entered Mexico markets.

NAFTA caused more mass migration north, displacing indigenous people from rural agricultural areas, and widening the gap between rich and poor. NAFTA doubled the amount of maquiladora workers and worsened environmental conditions in Matamoros and Brownsville. Colonias and maquiladoras embody the bleeds of the histories of capitalist pratices and neoliberal policies … environmental exploitation and racism along the border. Workers needed spaces to settle and colonias became those places. Colonias are small lots of 1950s agricultural lands, sold without any of the required basic infrastructures (drainage, electricity, sewage or potable water), located outside of towns. Colonias were sold by anglos who not only profited but also maintained the Mexican workers clearly separated without receiving any of the required cities’ public services. In 2008, with one of the strongest recorded natural disasters in the RGV, Hurricane Dolly affected colonias the most. (From Crisis to Change Curriculum)

As industrial mass agriculture became the economic base, toxic pesticides were used for large scale farming. This caused farm workers and their families in proximity to the farms to suffer from health issues. In Mission, Texas, a large number of cancer cases were recorded after the Hayes-Sammons Warehouse operated between 1945 and 1968 housing commercial pesticides. Today, some colonias are located near rental Pioneer farms, who produce unhealthy, GMO crops and harmful pesticides. (From Crisis to Change Curriculum)

4. The Perpetuated false promise of progress

In the next section you will learn about the main current environmental extractors in the Rio Grande Valley Delta. The main extractors now are connected to the extractors of the past. Here we want to unpack the promise of economic progress. The narratives used by Eurpoean colonizers to justify the pillaging and violence was that the Native Americans who already inhabited this land were primitative and that they came to bring “progress”. The narratives used by Stephen F. Austin to settle what is not known as Texas was the idea of “land as empty” and “manifest destiny” the U.S god given right to expand westward. *See Section 1: Dismantling Settler Imaginaries. The narratives used to justify mass agricultural expansion in the early twentieth century started with “there is nothing here.” The Valley was defined as “economically worthless and culturally backwards” for Anglo farmers and investors to make profit from the land. (9. Inventing the Magic Valley) *See Section The Magic Valley Boosters & Settler Place Myths

Today, we see the remnants of more than 100 years of mass agriculture in the Rio Grande Valley and the concentrated wealth built off segregation, land theft, and Mexican labor. According to the Texas Observer, as of 2018, two thirds of farmland is owned by white residents who also control the water. In this 100 years case study, we see that the economic prosperity promised by the Magic Valley idea was meant only for a few anglo families. The wealth did not trickle down. Hidalgo and Cameron counties continue to have one of the lowest income counties in the country. Structurally, families are economically poor because there has been a consistent historical extraction of wealth in the Rio Grande Valley Delta. People here are not backwards or ignorant, we are generations that have suffered from layers of wealth extraction and exploitation.

LNG and SpaceX are promising economic prosperity and progress to this area. Our history tells us this narrative is a lie. Why does economic prosperity have to come at the cost of the environment and the health and displacement of the people inhabiting the area? Who gets to impose the future for this area? Who gets to imagine the future? *See Section 13: Now

References:

6. How Race is made in America, Natalia Molina

9. Inventing the Magic Valley,

Free Download https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230264017_Inventing_the_Magic_Valley_of_South_Texas_1905-1941

10. Harvest of Empire, Juan Gonzalez

Links:

ADD LINK (From Crisis to Change Curriculum)

ADD LINK (LNG Report).

https://guides.loc.gov/latinx-civil-rights/bracero-program

https://www.texasobserver.org/the-making-of-the-magic-valley/

https://www.cameroncountytx.gov/economic-development-demographics/

During the 1960s, Américo Paredes, born and raised in Brownsville, Texas, brought to light research of the Texas Ranger violence and corrido tradition in South Texas as a form of resistance. His writings helped inspire the Chicano Movement of the 1960s, which uncovered histories of violence and injustice, and revealed patterns in U.S imperialism and violent treatment of Mexicanos and Native Americans in the United States. Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta, and the United Farm Workers organized strikes and boycotts against major mass agricultural industries and fought for the rights of farm workers, and against toxic pesticides. The United Farm Workers made their way to South Texas, founding LUPE, the Raza Unida Party would be formed here, and Latinos would win critical seats in South Texas government. The Chicano Movement of the 1960s would inspire and ignite Mexican Americans to look into their roots and history, in order to keep fighting for justice.

For Rio Grande Valley Civil Rights History — look at Nosotrxs Por El Valle

We are in a critical moment in present history. We are in the middle of a movement in the Rio Grande Valley Delta: a moment where we see the clear intersections between border militarization, U.S Imperialism, and Environmental Justice. This movement is about defending our inherent right to inhabit this land and our right to protect it against environmental destruction. We are on the frontlines of defining not only the future for this area, but informing what our collective futures will look like globally. History gives us a roadmap to explain our current political and socio-economic climate.

Nuestra Delta Magica Foundational concepts to keep unpacking

Agribusiness, labor, and deportation go hand in hand.

In the United States, official history reiterates how Mexican immigrants have been consistently exploited both as cheap labor and scapegoated for many of the country's economic shortcomings. In the book, Migra, Kelly Lytle Hernandez, writes about how border patrol surveillance historically intertwines with agribusiness. The Border Patrol was established during the expansion of mass agriculture in 1924, and it became, since its inception, an agency that wanted to control the labor of the Mexican migrant by instilling fear and threat of deportation. (13. Migra) During the Great Depression (1929–1939), U.S Americans blamed Mexican immigrants for their lack of work. A mass deportation military-like action called Operation Wetback deported and displaced about 2 million Mexicans that included US born and US naturalized Mexican Americans. Paradoxically, this action occurred parallel to the Bracero Program (1942-1964), a US-Mexican bi-national initiative that recruited Mexican workers, all male and without their families, on short-term contracts in the U.S. which brought more than 4.5 million Mexican laborers to work primarily in Texas and California. Consequently, US Immigration policy has been shaped around the need for labor. (6. How Race is made in America)

Our work to unlearn the official history does not stop in learning about erased Texas history or even US history. Learning the untold history of U.S imperialism and expansion into the Global South and the rest of the world will help explain the current social landscape of the Rio Grande Valley Delta.

2. The United states is an imperialist country and its wealth was and is extracted from other countries

In Harvest of Empire, Juan Gonzalez cites US imperial intervention in Latin America as the reason for mass migration to the United States. The United States hunger for expansion rooted in colonization and Manifest Destiny led to the continuation of greed, stealing of land, and expansion of U.S investments in Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and other Latin American countries into the early 20th century. The US government intervened and backed violent dictatorships in Latin America. As a pay-back, these regimes protected U.S investments, destroyed democratically elected governments, increased disparities between rich and poor, and opened the doors to more U.S exploitation of natural resources. Domestically, in South Texas, we see the bleeds of Anglo land theft through the U.S intervention of Mexico and expansion of U.S investments in Mexico, marginalizing rural indigenous communities and rural agricultural workers. We see this further bleed into neoliberal policies of free trade, continuing to displace and uproot people and exploit natural resources (10. Harvest of Empire).

NOW

NOW.

There have been layers upon layers of land extraction and environmental destruction in the Rio Grande Delta. For centuries, colonization, border and militarization, racism and violence, and environment destruction have made the Rio Grande Valley Delta a sacrifice zone. Sacrifice zones are defined as areas with a high amount of environmental extraction and economic divestment, and are typically areas that are predominantly people of color. Racism and environmental destruction are inseparable. Today, the Carrizo Comecrudo Tribe is leading the protection of air and water, and their ancestral sacred sites in South Texas. The main extractors that the Estok’ Gna people are resisting are LNG (Liquified Natural Gas), SpaceX, and the Border Wall.

LNG

Texas is synonymous with big oil and the Rio Grande River is one of the most polluted in the United States. Today, there are more miles of oil and gas pipelines than there are road according to environmental activist Bekah Hinojosa.

LNG stands for Liquified Natural Gas, and it is extracted through a process called hydraulic fracking, which uses an incredible amount of energy, water, and chemicals. Fracked gas emits high levels of methane gas, which warms the atmosphere 80 times over than carbon dioxide. (LNG study) The United States plans to continue to expand fracked gas extraction projects, despite signing the Paris Climate Accord. The Paris Climate Accord is a historic agreement and commitment between nations all over the world to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in order to slow climate change. The Paris agreement’s goal is to limit warming to 1.5 degrees celsius, but studies now show that a complete end to all fossil fuel expansion is critical in meeting this goal. This information comes from a 2022 report signed by the Sierra Club, the Rainforest Action Network, Les Amis de la Terre France, Save LNG from RGV, and the Carrizo Comecrudo Tribe of South Texas. You can download the study here.

There are two LNG export projects that are being proposed to be built at the Port of Brownsville and one pipeline.

● Texas LNG, owned by Glenfarne Group, Samsung Engineering Co, and Texas LNG;

● Rio Grande LNG, owned by NextDecade;

● Rio Bravo Pipeline, owned and operated by Enbridge.

● Valley Crossing Pipeline, an existing pipeline that

would also service gas to the LNG projects, owned and operated by Enbridge.

Screenshot taken from Rio Grande LNG advertising on Facebook

LNG companies are using greenwashing, a tactic to market their type of fracking as more sustainable and beneficial to the community and environment. Their marketing campaigns are targeting Rio Grande Valley residents, saturating local residents with social media ads promoting fracking as good for the community. One of these promotional videos shows Jerry Briones, Chief Operating Officer of the Greater Brownsville Incentives Corporation, declaring that LNG will be great for community schools and small business, claiming that it will create 5,000 jobs. (LNG Report)

Rio Grande LNG plans to build their plants on the sacred land of the Carrizo Comecrudo Tribe of Texas. In addition, the LNG projects will affect the pristine Gulf Coast of the Rio Grande Valley, with undisturbed wildlife and a thriving ecosystem. The LNG projects would destroy the habitat for endangered wildlife including the ocelot, northern Aplomado falcon, the Rice’s Whale, and Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle. (LNG Report).

You might question whether there has to be regulatory processes for preventing huge and devestating impacts of extraction. The issue is that these oil and gas companies manage to bend the rules, read more here:

https://www.sierraclub.org/texas/blog/2018/07/valley-crossing-pipeline-exercise-corporate-trickery

SPACE X

Tribal Chairman, Juan Mancias in front of SpaceX Testing site rocket

Screenshot taken from Trey Mendez personal Facebook account

Corrupt officials and complacent wealthy elite are putting in place policies that are affecting and may destroy the ecosystem in the Rio Grande Valley Delta. Former State Representative for Brownsville, Rene Oliviera, advocated passing House Bill 2623, which gave power to Cameron County to temporarily close Boca Chica Beach for space flight activities, bypassing the state Open Beaches Act, which protected the gulf and made it accessible to people all year long. Cameron County commissioners passed a decree to exempt Space X from paying 10 years of county taxes. GBIC, one of the economic arms of the City of Brownsville, has created incentives to space developing companies, and together with the City’s support have branded Brownsville as the new space city, imposing a colonial-subaltern identity onto the majority people of color population. One of the outcomes of this branding is rent going up and people must already relocate and are getting displaced, exacerbating the existing housing crisis in the lower Rio Grande Delta.

SpaceX restricts access to a public beach, is destroying wetlands and vital habitats, is causing large wildfires, and is requesting to dump 200,000 gallons of treated waste and sewage water per day into the bay. One of the latest rocket launches caused the ground to shake forming a small earthquake that unsettled most of Brownsville, Texas.